An AI Can Never Get Drunk

Suboptimal gambling at the end of the world

For the elevation of the soul of Dalya Davida bas Yisroel.

One evening, as I was running late for a meeting at a coffee shop, it hit me: I have never, in my entire life, intentionally and willfully deviated from the optimal path chosen for me by real-time GPS.

The problem with ChatGPT is not that it makes mistakes but that it cannot make a mistake. The term “hallucination” is also far too humanizing. An AI only “makes a mistake” in the sense that it does not produce our desired outcome. When my car engine overheats, is the vehicle “in error”? When the hard drive of my childhood Compaq became corrupted and the operating system degraded, was the machine “hallucinating”? A broken thermometer is not “in error about the temperature,” except as a turn of phrase. Its physical state is always a perfect reflection of its inputs and causes. The mercury always rises or doesn’t rise precisely in reaction to its physical antecedents. It is always 100% “right” because it can never be anything other than a consequence of the laws of physics operating on it at any given moment. It is only “broken” when it gives the “wrong” temperature. In other words, when it no longer serves the entirely extrinsic purpose assigned to it by the artificer or user. A malfunctioning AI is broken in precisely the same way. There is no “internal state of mind” misaligned with reality; ChatGPT can no more be “misaligned with reality” than some mercury in a glass tube or beads on an abacus can be “misaligned with reality.” If AI’s lack of true internal states doesn’t matter—if all that matters is functional resemblance—why smuggle in language that tricks us into treating it like a mind?

The instinctual reaction of the AI faithful to this idea is to declare that the human mind must not be capable of error or hallucination either; that we also cannot be “misaligned with reality.” Indeed, this statement has a certain pleasingly Buddhist ring to it. But this argument collapses under its own weight. If humans, like machines, cannot truly be wrong, then truth itself is meaningless. The entire enterprise of science, including the claim that humans are mechanisms, assumes truth is real and knowable. But if we are only machines, then we are nothing more than broken or unbroken thermometers—we don’t know anything; we merely process inputs. To claim that human beings cannot be wrong, but merely broken, is to erase the very foundation of knowledge.

If the maker of the thermometer cannot be “wrong” but only “broken,” then the science of measuring temperature can never declare a hypothesis “wrong”, either. The scientist, too, is just physics acting upon physics. The most they can say is that certain inputs appear to produce certain outputs. But even this “seeming” is just another consequence of physical processes in their brains. There is no “truth” or “error”—only functions and malfunctions. But what would it even mean to call a brain “broken”? We’d have to ask its artificer. And if the human brain has no designer and is just an accident of matter, there is no standard by which to judge whether it’s broken or whole. If we can’t say whether a mind is broken, we cannot tell if it ever knows truth. Therefore, the very act of measuring the temperature correctly becomes impossible—we are bound only to output whatever inputs reach our brains. No evaluation can occur. Thus, the very science that seems so eager to declare us mechanisms can only make its argument if we are not mechanisms. A thermometer, or an AI, can only be broken if human beings can be wrong. And if the reduction of the human soul to a mechanism isn’t science, what is it? What special credence should we give to technologists who approach us and declare axiomatically that being mistaken is a meaningless concept?

The sane and rational position is rather: AIs cannot make mistakes or be in error; they can only reflect their inputs. The human mind does not work this way. We are all, in our subjective experience, familiar with our ability to know the truth. Our mind is not just a summation of physical causes but is self-aware and intentional. An AI is a vast and impressive and deeply useful statistical function that presupposes no ability to “align with reality” whatsoever. To be wrong presumes an intentional relationship with truth; it requires that a mind be oriented toward truth as a normative ideal. AI has no such orientation—it does not “err” so much as produce outputs that do not match externally-imposed expectations. It is just a very, very complicated thermometer. By contrast, the human ability to know, to seize upon our own physical antecedents and make sense of them, totally apart from extrinsic standards of judgment, is one of the most common human experiences. It also underlies all of our thinking. Even a mechanist must assume that human cognition tracks reality meaningfully; otherwise, all scientific claims (including mechanistic ones) become unintelligible.

Functional equivalence never yields intentional meaning. A calculator may output correct (or incorrect!) sums, but it does not grasp mathematics. It has no concept of numbers, truth, or proof. A text generator may string together words in meaningful ways, but it has no concepts to express. It is even impossible to say whether it is serving its intended function—whether it’s broken or not—without consulting the one who made it. AI may generate human-like responses, but it doesn’t know anything. A computer does not think. A boat does not swim. A mirror does not see. And no matter how advanced it becomes, AI will never understand what it reflects.

Culturally, the AI’s inability to make mistakes or hallucinations furthers a certain self-imposed subjugation-through-optimization we had already implemented through social media. Of course, following the tribe, the crowd, or the idea is as old as humankind and the foundation of the perennial temptation to idolatry. The ability to not follow the crowd—whether the crowd of sensory inputs playing across our biological needs and psychological structure to push us to certain acts, or the mob of people who can give us protection, belonging, and purpose in exchange for sacrifices—is one of the powers unique in creation to humankind.

What has changed in the new millennium, as Jon Askonas has brilliantly explained, is that we now believe there is one objectively and quantifiably optimal answer or course of action. It is the one fed all the data, crowd-sourced and vetted by millions. I want five thousand reviewers on Amazon to tell me that this tea is better than that tea, and the aggregate score tells me precisely how much better my life could be. Expand this logic to every facet of my existence—my job, my doctor, my therapist, my reading, my god. Everything can be optimized, rated, and ranked. I can push, scrap, and grind for a five-star, 10/10 life. Add in LLMs, which let me perfect not just the broadest choices but the tiniest details, according to all the correct decisions of all the human beings whose words were its dataset. Instead of a golden calf to soothe my insecurity, I have a black box. I will escape the burden of choice. I will never be wrong. I will soon be as happy as it is mathematically possible to be.

The nerds, left to their own devices, will form themselves in the image of their machines. They will not only believe that AI defines intelligence but that what AI cannot do, intelligence itself cannot do. This is the tragic outcome of optimization for fitness and immortality, as it always has been and always will be. We often forget that without an intentional and constant awareness of the createdness of technology, its non-totality, we quickly conform to its image. Eventually, the only humans who believe in human freedom become normies, and they certainly don’t remember the lesson, and the cycle repeats. The only way to reliably and consistently break the cycle is through the rebellion that Chassidus calls “choosing the King,” which means, really, to see that there is nothing but the King to choose, that G-d Almighty is the axiomatically real creator.

The G-d of monotheism serves a unique role by being an “anti-idea” idea, and all technologies, even holy technologies like the Oral Law, must be pursued with an awareness that they are created and therefore can never be all-determining. The unknowable G-d, whom one can never fully “pocket,” forces us into a deeper, unknowable self-definition and rescues us from becoming the effect of the tools we cause.

The Rambam, in the Laws of Repentance, writes a primary Jewish treatment of non-optimization: “The weighing of sins and merits is only carried out according to the wisdom of the Knowing God. He knows how to measure merits against sins.” Not only can we not optimize for merit, but we don’t even know how, and it would be wrong to try it. The 613 categories of obligation redound on us equally, as a whole. They are 613 facets of a single Divine Will. It is strange to contrast the simple givenness of this equality in the life of your average observant Jew, who might otherwise be very excited to optimize the quickest way to the synagogue or the best exchange rate for Chase Miles. There are certain forms of efficiency built into the Law, no doubt, where we choose one commandment over another for any number of reasons, including that it is the one most readily available. However, the justification for such choices is always a Torah justification, working within the bounds of its logical system; the idea of optimizing for piety points as an individual using some objective mitzvah comparison system is not just an absurdity but possibly an abomination.

The relationship with G-d, like any other relationship between actual selves, suffers in metrication and optimization. If a system of rules could capture a self, a self would not be necessary; G-d made us like him, rather than mere train stations for causes and effects. Of course, the part of Torah that most emphasizes this truth both about G-d and about our souls is Chassidus—it is, in fact, a Chassidic obsession. The holy Baal Shem Tov was famous for patiently explaining to simple, uneducated, suboptimal, inefficient Jews that G-d desires the heart, that their simple deeds done with sincerity—rather than schemes—are immeasurably precious to G-d.

Many rabbis hated him.

A teacher of mine once remarked, not flippantly but in seriousness, that Chassidic Judaism can be defined as the only monotheistic religion in which the consumption of alcohol is a core component. The Alter Rebbe refers to the future time of messianic redemption as “the day that is entirely mashke,” that is, alcohol. He says, “If drink proceeds inappropriately, it lowers one down, and one becomes lowly and shameful, but if it proceeds appropriately, it can greatly assist. Drink has warmth in it…the blessing is that it should warm the soul.” Alcohol is warmth, and life, and warmth and life are the qualities of G-d, whereas coldness and detachment are the qualities of death. Granted, alcohol also (as the Alter Rebbe also acknowledges) comes with a spiritual danger commensurate to its spiritual potential. But the point stands: the future era, flooded with the knowledge of G-d, will not be one of sober, platonic, objective truth. It will be thoroughly drunk.

Hear how drunk Chassidus is: unlike some communities of observant Jews, where the opportunity to become someone (for example, the head of a Talmudic academy) is dangled as the carrot for students to be diligent and work hard, there is no program of study or self-refinement to become a Chassidic Rebbe. Certainly, setting it as one’s goal makes it thoroughly impossible. Not everything is the result of a goal-directed process. Not everything is partial, externally defined, and arrived at through an intermediary. In this, too, the more profound possibility for respecting a human being is derived from the deepest form of respect for G-d. Both are forms of respect that to their detractors, for whom sobriety is the highest value, constitute disrespect. If you say, “A Rebbe just is a Rebbe, and no hours of hard effort or toil or good behavior make you one,” you take away the standard by which everything is judged. G-d Himself only gets an exemption, if He does, by being the Creator of the standard. Of course, Chassidus agrees with the Rambam that no knowledge of G-d’s creation ever amounts to the real understanding of G-d. Reality is more disjointed and more absolute than one might assume, and a neat optimization and ordering of things is quite beyond human reach. Chassidim don’t find this insulting or depressing; on the contrary, it is the greatest honor and the greatest joy. Something is truly beyond the reach of corruption by my finite, false standards. Something is true just because it is true, without my help or consent. Something is known not by negotiation or journey or accretion of accomplishment. Something is known through the most substantial possible sacrifice: letting it in without imposition, as I let myself in. Something is immediate. Something is here now, if I can but lose the game.

Here is what ingested alcohol, whether as liquid or as Torah, accomplishes at a Chassidic farbrengen, or gathering: we slowly let go of our standards, and the “me” disappears. My fellow Jews are together with “me” only inasmuch—inasmuch as they agree, inasmuch as they’re nice, inasmuch as they’re smart, inasmuch as they don’t smell, inasmuch as I’m in the mood. Our relationships are partial and transactional even if we are committed and kind. The warmth wears away at the rules of this game. The molecules at the surface vibrate out of place. Things liquefy. We are vulnerable in ways we’d perhaps prefer not to be. We cannot keep ourselves out of others and others out of us with quite the same skill. We are shockingly, disturbingly, together. A man criticizes himself and others, and we are not sure which is which. We forget who we dislike and who we do not. Some oddly familiar, confident, and invulnerable Jewish spectacle rises within us to the music, and the doors of Divine surprise are thrown open. Cliches we normally reject fall like freshly-polished thunderbolts. Even as we say, truthfully, that it would hurt too much to change, we see how we can change without it hurting too much, and commit to remembering it in the morning. We feel brave and tall.

We step out into the night, imperfect, having wasted time drinking with our friends that could have been spent studying. The stars sing joyous absurdities, and we are warm all the way home.

“We were as dreamers,” says the Psalmist, and the exile follows a fragmented and absurd dream logic. Its madness cannot be fought with sobriety, but only with good madness, and every Purim is the best Purim in history to have a drink.

Does the world seem mad? Not just mad, but so deranged we are almost unable to describe its madness? Good. Perhaps we are realizing that we are dreaming, that our optimal outcomes are dream outcomes, that we do not exist to dance to exile’s tune driven by greed for its exile riches and fear of its exile consequences. The madness every living Jew with a brain and a warm heart now knows well is the dissonance born of our sense of exile security being lovingly stripped away piece by piece. Because exile is out of answers and is dying before our eyes.

The Jewish concept of exile, of course, is not just about displacement from our land, although that is the traditional litmus test. It is a cosmic state of disorder and darkness in which the world is asleep to its inherent nature as a place of beauty and repose for the Divine. The chaos dream is impossible to fix from the inside because the methods of repairing it are of it and tainted by it. Our political, religious, and technological solutions are all tired and despicable. Exile is a guaranteed temporary state of affairs. All paths within it culminate in its ending. All shall be redeemed. All will burn. It is not a question of "if," but a question of when, and how, and at what cost. Will we come willingly, or kicking and screaming?

The first step is to realize that we are in exile and there is something broken about the world that the world cannot fix. The second step is to use what reaches us of redemption to live above its brokenness, as if the redemption is already here. The third step is that the brokenness of exile itself must become the very material of redemption.

The Jews, on the whole, are confident that the end of this exile is not far off. The world is changing rapidly, though falling apart may be a more accurate term. And that's not necessarily a bad thing. We are not going to get there with our current meanings wholly intact. This long brokenness feels like it's deep in a state of decay. Its explanations for itself and where this is all going are wearing thin and fanciful. We’ve already watched the impossible become fact. We will probably see it many more times.

It is helpful to contemplate how what is left of our intellectual discourse is not about "finding G-d," which in retrospect would never entirely work because the exile brain can only find the exile's conception of G-d. We rejected this conception in a movement called "modernity.” Instead, our life of mind today is about very studiously and thoroughly "unfinding" the exile.

Most of our kulturkampf is over slight dialectical differences in this process. Civilization is a piano that has already fallen off the roof. The "left" and "right" differ the breadth of the harmonics of a single string. We're fighting over the tone that rings in the wreck. As we must, because there is nothing else left that makes any sense at all.

The postwar order, faith in planned secular progress, trust in institutions of all kinds, humanist consensus, the very coherence of the concepts of "left" and "right," the authority of science, every social contract and narrative, shared realities of space, time, and meaning...all our answers are self-refuting. One more democracy, one more expert, one more technology, one more social justice, one more monarchy, a higher GDP, more sarcasm, and more science fiction. One more machine optimizing for that perfect answer. These will certainly fix it all.

One more religion, one more theology, and one more spirituality—none of it will save us. This is not a pitch for being good boys and girls and eating our vegetables. It’s not a problem to solve for. There is no mathematically optimal path across the face of this collapse. Not only is G-d dead, they killed His death, too. Nothing "works" anymore. Perhaps you feel it too—the collapse of all meaning, even the curiously successful and profound negative meanings of the past 500 years.

It is terrifying.

But the exile deserves to die.

And so we arrive back to the beginning, at the original exile story, at Purim. The sin of Purim was optimization. The mitzvah of Purim is getting drunk.

The sin of Purim was to cozy up to the wicked king because the Temple was destroyed, our existence was playing out on the edge of a knife, and we had driven G-d away. The mitzvah of Purim is Esther, non-optimal, haggard, exhausted, and dehydrated, appearing before the king. The people fasted for three days and pinned their hopes on something ridiculous, unknowable, and probably long-gone, that is, the G-d who used to defend their borders and burn their sacrifices. They were decidedly stupid, caught up in a non-strategic madness that refused to recognize G-d’s hiddenness, which in turn broke through the dichotomy and showed that G-d’s non-existence in Persia was in fact G-d’s existence in Persia and all things both denying and affirming G-d belong to Him because He is what He is and not defined externally. The Jews of the book of Esther are drunk because they refused to play the game the world told them was the only game to be played. It is in the heart of all-encompassing doubt when all meaning is meaningless that an embrace of the “meaninglessness” of wild commitment gives birth to redemption. And that is how a Jew survives in exile.

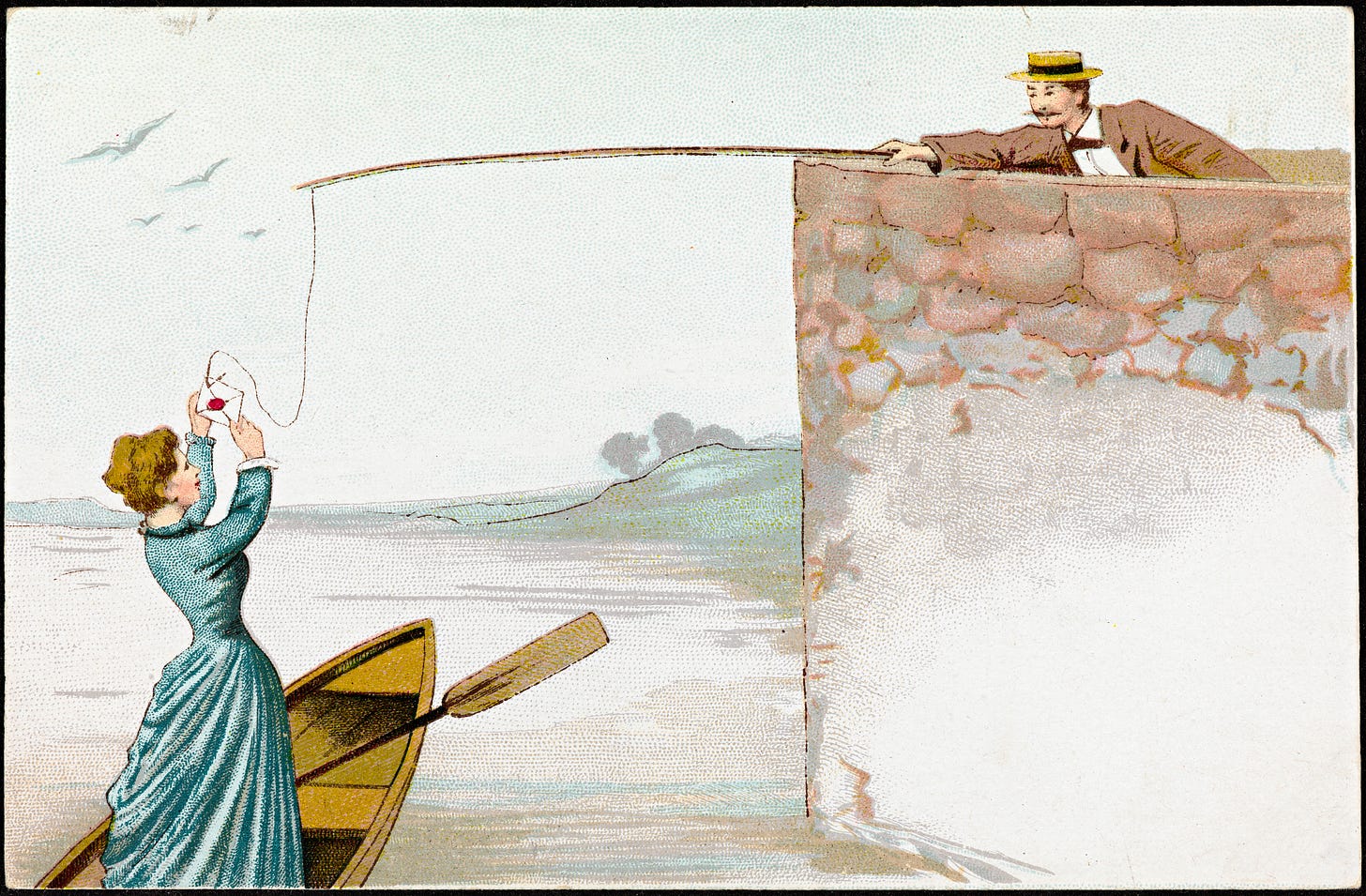

It strikes me that even secular Western civilization once knew that falling in love is not a simple pragmatic structure and, on the contrary, is often a pointless act of self-destruction. That it is indefensible to others and the only thing that’s real to the parties involved. That is undignified and stupid and not proven in a peer-reviewed journal. But they only knew this with exile logic. We drink to know this all the way down to the foundation of redemption.

I once learned with a student just home from his first year away at yeshiva after high school. He asked why anyone would be any particular group within Judaism—why would you be Chabad? It is a very good question I ask myself all the time, but it soon became clear our premises differed. He was asking, Doesn't choosing one Rebbe make you close-minded? I told him that being a Chassid is like falling in love, and as long as you're optimizing, as long as you’re trying to come away from this Judaism thing with the very best thing for you and your life, you will never understand it.

I should have told him that Meir Abhesera used to write love letters to the Lubavitcher Rebbe. I should have told him about Hillel Paritcher's vort on Shir HaShirim. I should have told him that the Rambam says our love for G-d must a constant obsession, like a man who cannot stop thinking about the woman with whom he is besotted.

He said, Wouldn’t you agree that some people get too carried away with the whole Rebbe thing? I told him that it is a far greater tragedy to close oneself off to the holy gamble, to surrender, risk, and sacrifice, than to have a few addled lunatics who cannot properly understand the relationship between Chassid, Rebbe and G-d. I should have told him that he would be told in a million small ways as he goes to college and studies the human condition that to be a wise adult, nothing must be sacred. That if he didn’t want to become a messenger of that truth, deformed by his technology, then he must commit to a holy discourse like a man wandering the desert commits to cold water.

He asked, How can you be a chassid of a rebbe who has passed away? I asked him, How can the Rebbe have passed away if nearly your entire Judaism (since he was raised in a Chabad house) is an act of that Rebbe after the Rebbe passed away?

He asked why he wouldn't just have a relationship with G-d instead of having a Rebbe. I told him that having a Rebbe is the sine qua non of having a personal relationship with G-d, that his notion of a personal G-d was literally given to him by a Rebbe through intermediaries, that the very person having the personal relationship is none but the Rebbe.

He asked why anyone needs a Rebbe, and I asked why anyone needed a Moses. He said, Well, we don't have Moseses anymore; prophecy is gone, and I said, The sages of the Talmud had their Rebbes and they treated them as Rebbes, and he said, Well that was then and this is now, and I said, Only because centuries of subjugation in exile have made us afraid of having Moseses because it means that our survival mechanisms and fragile sense of security would necessarily have to go and we would need to become strong and brave.

The truth is that you never know, and you need to trust, and real Judaism is a risk like a risk you take on a person, and studying the inner torah is like falling in love, and academic detachment in this is a total waste of time. We must gamble everything, as the Holiday of Lots teaches us. In 2025, there is no other way. We must be sub-optimal. We must drink. We must love one another or die.

Note: This essay was written by an imperfect and lost human being with the assistance of a very sober ChatGPT.